Farmers benefit greatly from the presence of bats. But these highly effective insect-eaters are facing some new and deadly threats

For many South Carolinians, a very relaxing way to enjoy a summertime sunset is to sit outside and watch the acrobatic maneuvers of bats in flight. What makes the show even more entertaining is knowing they’re gobbling up half their weight in insects.

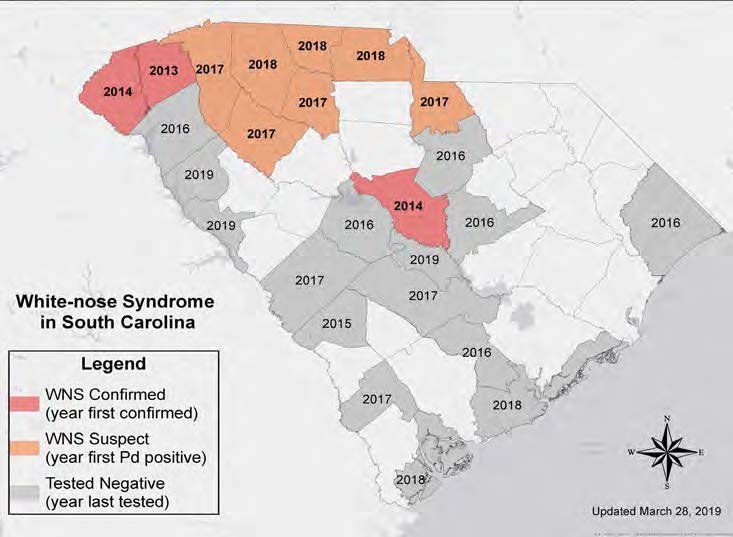

If you’ve noticed a decrease in the number of bats over the past few years, then you’re seeing the result of habitat encroachment, changing climate and, most recently, white-nose syndrome (WNS).

It’s estimated that more than six million bats in this country have disappeared since 2006, and more than 50 percent of bat species in the U.S. are either in severe decline or are on the endangered list.

According to Bat Conservation International (BCI), there are 47 species of bats in North America. South Carolina has 14 species, including the big brown bat, Mexican free-tailed bat, tri-colored bat, eastern red bat, eastern small-footed bat, evening bat, hoary bat, little brown bat, northern long-eared bat, northern yellow bat, Rafinesque’s big-eared bat, Seminole bat, silver-haired bat and southeastern bat.

Sorry kids, no vampire bats in these parts...

While bats in the Palmetto State face many threats, the newest danger is a seemingly harmless fungus that causes a fatal disease called white-nose syndrome.

WNS is caused by a fungus that appears as a white fuzz on a bat’s face and other exposed skin. The fungus, Pseudogymnoas cus destructans (PD), attacks the bare skin of bats while they’re in hibernation. Infected bats grow uncomfortable and become more active than normal, burning fat they need to survive the winter. You could almost say they go stir-crazy as stricken ones are often seen flying aimlessly during midday hours. Unfortunately, starvation followed by death are usually the final results. At some roosting sites, 90 to 100 percent of bats have died from the disease.

If you raise row crops or timber, you may have noticed the decrease in bat populations in a monetary way. Bats play a key role in pest control, which can be a major expense for farmers. They also help with pollination, seed dispersal, soil fertility and nutrient distribution.

I recently spoke with Susan Loeb, Research Ecologist for the USDA Forest Service Southern Research Station at Clemson. Susan has studied bats for more than 20 years. While she concentrates on South Carolina, she is in contact with bat specialists around the country.

“There have been several estimates in an eight-county area in Texas that the free-tail bat can provide several million dollars of pest control services per year,” Loeb said. “That’s based on the number of insects they consume as well as the reduction in the amount of pesticides farmers have to apply to their fields.

“So, someone has extrapolated those numbers from that eight-county area and has come up with an estimate that across the U.S., bats provide more than 23 billion dollars in pest control services every year.”

Loeb qualifies that statement by reiterating that it’s an extrapolated number, so it should be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, it’s clear that bats are an extremely valuable part of modern agribusiness.

That’s one reason Clemson has taken such an interest in white-nose syndrome. First discovered near Albany, New York in 2006, the disease spread northward into Canada then down into the Midwest before turning south along the Appalachian Mountain chain.

In 2013, WNS was discovered at Table Rock State Park. Today, it is primarily found in the Upstate of South Carolina, where a mountain tunnel provides Loeb and her team an ideal laboratory to study its effects on bats.

“To give you an idea of what kind of mortality we’ve had, there is a tunnel in the Upstate called Stumphouse Tunnel. In 2014, it was home to 321 tri-colored bats. This year we had 31. So, we’ve had about a 90 percent decline,” said Loeb.

“Similar numbers have occurred over in Georgia by Clayton. They went from about 5,000 bats down to 200. We are seeing huge mortality in some of our species.”

Loeb explained that some species are not being affected. Common species such as the big brown bat, the red bat, the free-tailed bat, the evening bat–those species are still doing relatively well in terms of white-nose syndrome.

“But of course, other things do affect them,” she noted, “like loss of habitat. It’s a big problem for our tree-roosting bats when we lose forests.”

Loeb said climate change may enhance the numbers of some species and negatively impact others. For example, the free-tail bat has been moving farther north.

“When I came to Clemson, there were very few free-tail bats. Now, there are tens of thousands of them living in places like Death Valley and a number of other areas on campus and throughout the Upstate. “This is a species that likes to live in human dwellings, like schools and churches. They seem to be doing well and seem to be moving north due to a warming climate, but we’re not really sure why. Other species may be moving north as well, resulting in fewer of that species here in South Carolina.”

Loeb went on to say that trees are affected as much as other agricultural products by white-nose syndrome.

“Bats eat a number of insects that affect both pines and hardwoods. Also, in terms of recycling nutrients, their feces are high in nitrogen and phosphorus, so they distribute those nutrients throughout the forests.”

Build Your Own Bat Hotel

There are several ways you can help protect bat populations, even in your own back yard. While most of us can’t cure white-nose syndrome, stop habitat loss or slow climate change, we can protect caves and roosts that harbor them. Even dead trees are favorite hangouts.

Another way we can help is by installing bat houses. You can purchase a pre-built bat house online for $15 to $50. Bat Conservation International provides guidelines for a proper bat house on their website, batcon.org. They also offer a list of manufactured houses that meet their specifications.

If you’re the DIY type, there are a number of blueprints and how-to YouTube videos to assist you. You can find an instructional video on batcon.org that takes you through the process. Just as important as its structure is its location.

So, next time you see a bat, tip your hat. Despite their spooky reputation around Halloween, there’s absolutely nothing to fear. That is, unless you happen to be a flying insect.