Originally published in the SC Farmer Magazine, Summer 2023 issue

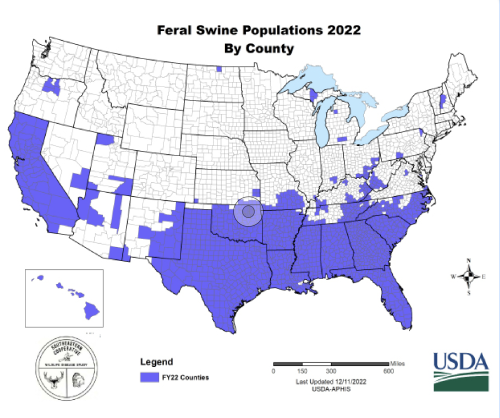

In the 1500s, Spanish explorers first introduced feral swine to America. Fast forward 500 years, feral hogs can be found in at least 35 states and now, in all 46 counties of South Carolina. And they’re a serious issue for farmers and landowners.

One mid-April morning, Rachael Sharp and her father Don were out checking their recently planted cornfields. “I noticed something looked a little off,” Rachael recalls. “We went on around the curve of the road and the damage was just incredible.”

This was the Sharps’ first experience with these destructive pests, and it surely wasn’t a pleasant one. All-told, the hogs tore up 224 acres of corn -– more than a quarter of their total crop. Rachael notes that they were lucky to have crop insurance, but even that couldn’t cover the damage caused by the hogs.

“Our crop insurance adjuster offered to pay for a few bags of corn to replant,” Rachael explained. “Not one week later, the remainder of the corn was gone, and the newly planted crop was completely mowed down. We explained to our adjuster what happened, and she truly didn’t believe us. Even with the crop insurance, we weren’t made whole. The damage these animals do to the land is unbelievable.”

Farmers across South Carolina have been battling the menacing wild hogs with increasing vigor for the last few years. Unfortunately, the swines’ prolific breeding and cunning keep them from being easily exterminated. Feral hogs destroy freshly planted fields, then ruddy the ground, making it nearly impossible to replant. They spread diseases to livestock and cause problems for landowners around the state. Their destruction costs farmers more than $151 million every year.

These impacts reach beyond the farming community; feral hogs are also destroying South Carolina’s natural habitats and harming various plants and other wild animals.

In a 2021 article from The State, Sammy Fretwell wrote:

“The agriculture department reports that wild pigs are hurting rare species. In Florida, one agriculture department report says wild hogs contributed to a reduction in 22 plant species and four rare species of amphibians. In South Carolina, hogs on North Island near Georgetown ate thousands of rare sea turtle eggs before hunters successfully knocked back the population… Forests are also being affected. The Francis Marion National Forest, for instance, is having difficulty managing the woodlands because of hog damage to the ground, [Rep. Sylleste] Davis said during a recent House subcommittee meeting.”

In the January/February 2021 issue of Shooting Sportsman, E. Donnall Thomas Jr. notes that while the impact on gamebirds has not been widely documented, the effects are certainly being noticed.

“A study from Texas A&M noted ‘evidence both circumstantial and direct that feral hogs can be detrimental to quail.’ Field studies showed that feral hogs were responsible for 10 to 30 percent of quail nest destruction… Studies with collared hogs also have shown that they develop ‘search images’ targeting quail, shifting their feeding behavior seasonally toward areas and habitats favored by nesting gamebirds. This behavior makes them even more efficient predators on quail and wild turkeys. Hogs don’t just have good noses. They are among the most intelligent mammals on earth

Feral hogs aren’t the only wildlife species causing problems for farmers. In a recent survey conducted by South Carolina Farm Bureau, farmers cited 15 different species that are responsible for loss of income. Wild hogs and white-tailed deer lead the way.

Because of the state’s rapidly increasing population and high development rate, some wild animals that have long co-existed with South Carolinians are now running out of habitat. This loss of habitat drives them to rural areas ripe with crops that make for easy pickings. In the same SCFB study, one farmer attributed $580,000 in losses because of wildlife.

While many anecdotal accounts exist, finding a true quantification of the damage has proven challenging. Enter Clemson University researchers Dr. Kendall Kirk, Dr. Cory Heaton and Ph.D. student, Perry Loftis.

In 2020, the trio completed a study to determine the cost of white-tailed deer to agronomic crop producers in South Carolina. Their research is multi-faceted and focuses on determining actual deer densities in agronomic regions and identifying yield losses in soybeans, cotton and peanuts. Thanks to funding support from the South Carolina Soybean Board and South Carolina Peanut Board, the team has been able to conduct research in the major production areas of the state.

Deer density estimates were obtained through spotlight surveys in Anderson, Barnwell, Florence, Richland and Orangeburg counties. Results of repeated years of surveys in these counties suggest the deer population is roughly 2.5 times higher than county numbers reported by the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. While deer densities vary among counties, deer density estimates in agriculture regions of the state appear to consistently be at or above 100 deer per square mile (1 deer per 6.4 acres). It should be noted that SCDNR estimates represent all suitable deer habitat for each county, not just agricultural areas.

The researchers studied soybean fields located within the spotlight survey routes. Exclusion cages were placed in the fields to prevent deer from eating crops in that area. Then crop yields were measured from both excluded and open areas in each field. The researchers concluded that deer damage costs soybean farmers 12.3 bushels and $172 per acre. Statewide, those numbers are a staggering 3.8 million bushels and $53.2 million.

At current commodity prices, the impact of deer damage is even greater per acre for cotton and peanut crops, which have an estimated average loss of $243 per acre and $188 per acre respectively. Statewide, this is a loss of 55.6 million pounds of lint per year for cotton, or $46.1 million, and the loss to peanuts is 63.2 million pounds per year, or $15.8 million. It is also worth noting that all three of these crops are top-ten commodities for South Carolina and these combined losses have a significant impact on the overall agricultural economy.

This year, the project will continue to investigate yield impacts across the state, along with surrounding deer population densities.

While the impacts of nuisance wildlife are well-documented, a solution hasn’t so easily presented itself. Several government agencies offer various programs to help mitigate the damage. Wildlife Services, a program within the United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, provides Federal leadership and expertise to resolve wildlife conflicts so people and wildlife can coexist. The agency strives to reduce wildlife damage to the lowest possible levels, while simultaneously reducing wildlife mortality by developing and using biologically sound, environmentally safe and socially acceptable strategies.

Wildlife Services has full-time employees whose primary duties are assisting landowners with evaluating wild hog damage to agriculture, natural resources and property. The federal employees use a variety of management tools to remove hogs from the landscape. The use of drones has been added in recent years to survey properties and assist with damage assessments. Additionally, their programs use a helicopter to conduct wild hog removal in the state.

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources offers several options for landowners to reduce damage from wildlife.

The Deer Quota Program issues “quotas” to qualifying landowners or lessees statewide who complete and submit an application along with a $50 fee prior to July 1. This program is generally better suited for landowners or lessees with large acreages.

Under the DQP, a quota of antlerless deer tags is issued to a particular tract of land based on criteria including density of the local deer population and its condition, the size of the tract of land, presence of agriculture or agricultural damage, and the overall deer management objectives of the owner. Participants in the DQP also have the option of receiving a quota for antlered bucks. These quotas are based on the average number of acres per buck harvested as reported by program participants in the county in recent years. The application period begins in May annually. To request an application call 803-734-3609 or email CastineP@dnr.sc.gov.

Depredation Permits for deer, beaver, etc. are normally issued at the local level by county game wardens. For assistance, contact the SCDNR Communications Center at 803-955-4000 and provide the operator with your name, county, telephone number, type of damage, and request a courtesy call from a county game warden.

Night hunting is an option to manage feral hogs, coyotes and armadillos. Night hunts may take place on a registered property on which a person has a lawful right to hunt, using any legal firearm, bow and arrow, or crossbow. This includes the use of bait, electronic calls, artificial lights and night vision devices. It is unlawful to hunt feral hogs, coyotes and armadillos at night on property not registered with SCDNR. Visit www.dnr.sc.gov/nighthunt to register a property.

The South Carolina General Assembly has enacted legislation in recent years to further aid in reducing the destruction caused by nuisance wildlife. On May 17, 2021, Governor Henry McMaster signed into law House bill 3959 that would help law enforcement more easily identify and prosecute individuals illegally transporting feral hogs. Lawmakers also allocated funding to aid in the trapping and removal of wild hogs.

A problem 500 years in the making will certainly need significant time and resources dedicated to its solution. Unfortunately, farmers seem to be the ones bearing the brunt of the burden. And farmers like Rachael Sharp are desperate for answers.

“Help can’t come soon enough for our farm and for everyone else dealing with this,” she says. “I hope we can find some relief – we could use it.”